- Call Us: 01-5970132

Hepatitis B is a serious clinical problem because of its worldwide distribution and potential adverse consequences.2 According to a World Health Organization (WHO) report, almost 30% of the human population or approximately two billion people present with serological evidence of either an existing or former infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV). Of them, about 350 million patients have chronic hepatitis B (CHB) and >1 million patients die each year of CHB that lead to cirrhosis and hepatic cancer.3Hence, hepatitis B is considered as a leading cause of liver-related morbidity and mortality, particularly in the Asia-Pacific region where the prevalence is as high as 75% of the world disease burden.4 India accounts for approximately 40 million people out of the global HBV infection pool of 350 million. Further, the epidemiology of HBV infection in India is in transition with nearly one million new cases per year. Moreover, with 3% carrier rate, India accounts for nearly 10% of the HBV carriers in the world, contributing to its rapid expansion. In this scenario, HBV epidemiology in India is likely to be an important determinant of the global HBV burden in the future.2

It is not surprising that China has the greatest burden of liver cancer in the world because one-third of the population with chronic hepatitis B lives in China. One in ten Chinese have chronic hepatitis B. China, one country alone, accounts for fifty-five percent of the liver cancer deaths every year from liver cancer. In other words, every year about half-a-million people in China die from chronic hepatitis B and many die at the prime of life.

Regarding Nepal we don't have exact data of HBV infection. However, our country can be classified as low endemic zone as per prevalence. Study carried out before 2-3 decades had shown 0.9% prevalence. Recent trend in Liver clinics of Nepal has shown that there is increase in prevalence.

Hepatitis B virus: The etiological cause

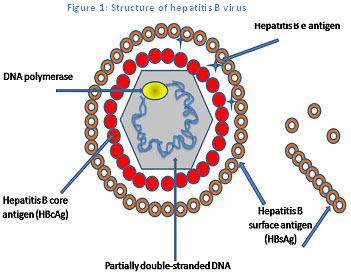

HBV, the cause of hepatitis B infection, is a hepatotropic DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) virus (Figure 1).3 The HBV is a blood-borne virus, which is transmitted from the infected person to another via blood and other bodyfluids. The transmission occur by various modes such as from an infected mother to the child during or shortly after birth, sexually or parenterally.5 The HBV infection may result in acute (short-term) or chronic (long-term) liver disease. Generally, the incubation period for hepatitis B is around 45–160 days.3

The symptoms of HBV infection can range from none to occasionally fulminant hepatitis and death within days or weeks of the onset of symptoms. The most common symptoms associated with HBV infection include abdominal pain, nausea, fatigue, dark urine, and jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes). However, nearly 75% of the patients infected with HBV remain asymptomatic. Adults are more likely to develop symptoms than children.3 The symptoms can be more severe in those who are immunocompromised or who have chronic liver disease.6

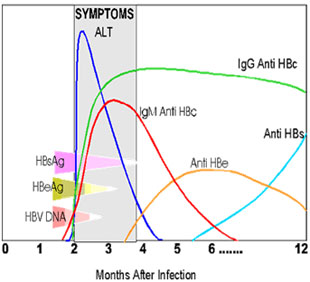

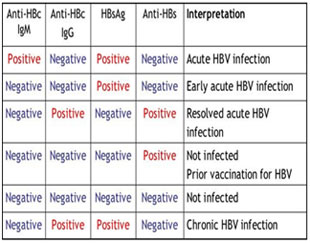

Clinical evaluationThe diagnosis of hepatitis B is based on the biochemical, virological and histological characteristics of HBV infection. Serological assays for the detection of HBV antigens (HBsAg and HBeAg) and antibodies (anti-HBs, anti-HBc and anti-HBe) signifies the disease progression. Further, liver function tests including serum bilirubin, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alubumin and prothrombin time levels are indicative of severity of liver disease. HBV DNA can also be monitored in serum by using polymerase chain reactions (PCRs)to assess disease activity and candidacy for antiviral therapy and to determine the response to treatment. However, liver biopsy is important to confirm the diagnosis, to recognize any comorbid disease affecting the liver, to stage the fibrosis and to categorize the grade of necroinflammation.6 Recently a non-invasive test called Fibroscan has been introduced. It can assess the stiffness of liver non-invasively. Many studies has shown that the results are comparable with liver biopsy results. Various serological markers and their properties arelisted in Table 1.7 The clinical course of these markers during hepatitis B is shown in Figure 2.8 Further, the clinical interpretation of hepatitis B based upon serological test results is given in Table 2.6

| Serological biomarker | Property of the biomarker |

|---|---|

| Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) | Surface protein contained within the lipoprotein coat. Indicates acute hepatitis, chronic hepatitis or carrier state. |

| Antibodies to HBsAg (anti-HBs) | Antibody to HBsAg, indicator of recovery/immunity to HBV infection |

| Hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) | Viral product secreted in blood, marker of infectivity, active replication (though absent in precore mutants) |

| Antibodies to HBeAg (Anti-HBe) | Antibody to HBeAg, denoting decreased infectivity |

| Hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg) | Core antigen (viral capsid), intracellular and not detected in serum |

| Anti-HBc immunoglobulin M (Anti-HBcIgM) | Antibody denoting recent HBV infection or exacerbation |

| Anti-HBc immunoglobulin G(Anti-HBcIgG) | Contamination marker, positive after HBV contact |

| Hepatitis B virus DNA (HBV DNA) | Quantitative indicator of virus in blood |

Figure 2: Clinical course of biomarkers during hepatitis B

Figure 2: Clinical course of biomarkers during hepatitis B

Table 2: Interpretation of serological markers in hepatitis B

Table 2: Interpretation of serological markers in hepatitis B

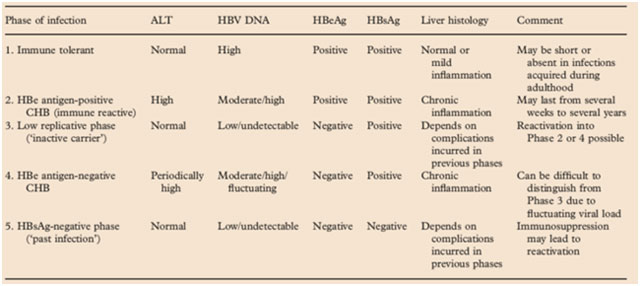

Hepatitis B can be a chronic disease which can gradually progress intohepatic failure or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).The natural course of hepatitis B infection can be divided into five phases,viz, immune-tolerant phase, immune-reactive phase (or immune clearance phase), HBeAg-positive CHB (low replicative phase), HBeAg-negative CHB, and HBsAg-negative phase (past infection phase). These phases are not necessarily sequential. Reversion or reactivation between different phases takes place commonly, making its clinical management challenging. The five phases are summarized below in Table 3.5

Table 3: Phases of HBV infection and clinical features

Management of hepatitis B: Whom to treat?

Table 3: Phases of HBV infection and clinical features

Management of hepatitis B: Whom to treat?

The decision to treat patient with hepatitis B should be based on reasonable clinical judgment. Largely, with current treatment options, viral eradication is almost unachievable for HBV. Therefore, only patients who are at risk for the development to advanced liver disease should be considered for treatment. Thus the basic treatment goals in hepatitis B are to achieve sustained suppression of HBV replication and remission of liver disease in order to prevent cirrhosis, hepatic failure and hepatocellular carcinoma.9

In clinical terms, the short-term goals of treatment are3

Further, the subsequent long-term goals of treatment include3

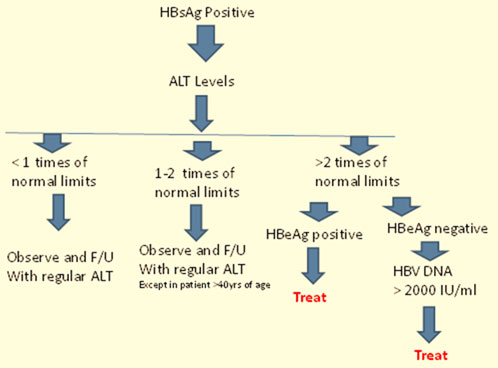

As per Asian Pacific Association for the study of Liver (APASL) 2008 guidelines, thorough evaluation and counseling are mandatory before considering drug treatment.10The clinical decision to treat a patient with hepatitis B is mainly based on HBsAg, ALT and HBV DNA levels.6 Patients with viral replication but persistently normal or minimally elevated ALT levels should not be treated. They need adequate follow-up and HCC surveillance every 3-6 months.10 Further, liver biopsy is recommended prior to therapy.10 Results of liver biopsy are also taken into consideration to characterize the grade of liver damage as a decision tool to treat patients who have elevated HBV DNA levels but borderline ALT levels or aged >40 years.10The potential candidates for treatment are further divided into two groups depending on the presence and absence ofHBeAg and are referred to as HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative patients, respectively.The differentiation becomes essential due to the contrast in treatment approaches for the two groups.6 The patients requiring treatment should show clinical signs of HBV DNA level >20,000 IU/mL in HBeAg-positive patients and >2000 IU/mL in HBeAg-negative patients along with ALT>2 times normal levels for both.10Additionally, all patients with cirrhosis, irrespective of the ALT level, need to be considered for treatment.6The treatment algorithm recommended by the APASL-2008 guidelines for patientswith HBV infection is outlined in Figure 3.10

Further, consideration of supplementary factors, including patient age, concurrent guidelines, medication compliance, liver disease activity, likelihood of long-term benefits, and potential therapeutic risks such as side effects, must be included as a part of the risk-benefit analysis during the decision to initiate treatment.4

What about putting treating agents?

Summary: